PEACE?

Just a couple of months ago I made two works – from the series of impermanent sculptures – that were apparently completely unrelated to any state of facts.

Both of them were verses from poems that I materialized by modeling them in materials that were easy to decompose while in nature.

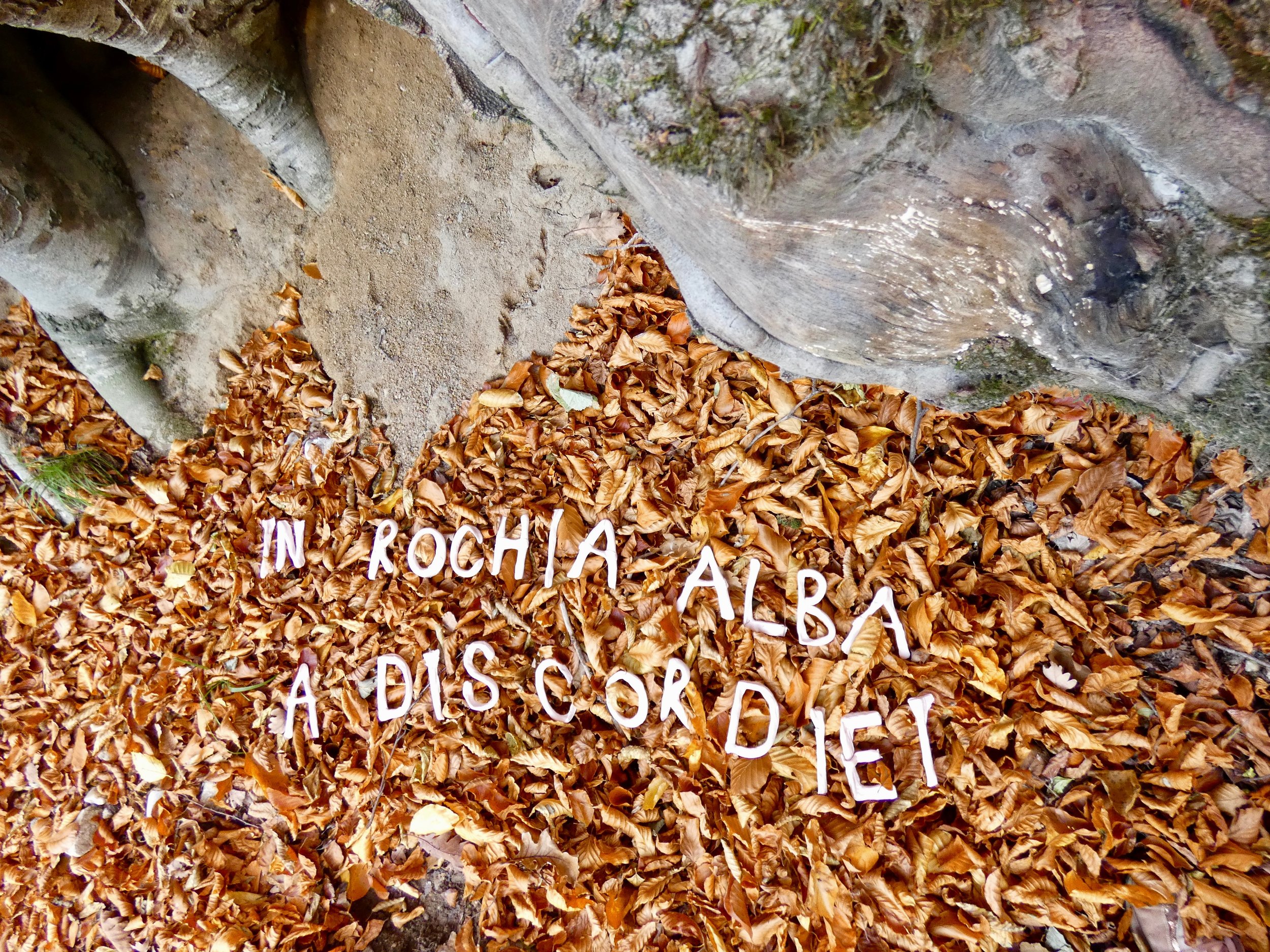

The first one said: IN THE WHITE DRESS OF DISCORD

It has its source in the image of the painting of Douanier Rousseau – War (1894).

I wrote first a poem, called Fear - On the Museum’s Floor. It dealt with our angst that can materialize, but we hope that can never be acted upon. The poem spoke about an imaginary sight of the war, as it was evoked by Rousseau’s painting.

IN ROCHIA ALBA A DISCORDIEI/ IN THE WHITE DRESS OF DISCORD - modeling clay, 2021

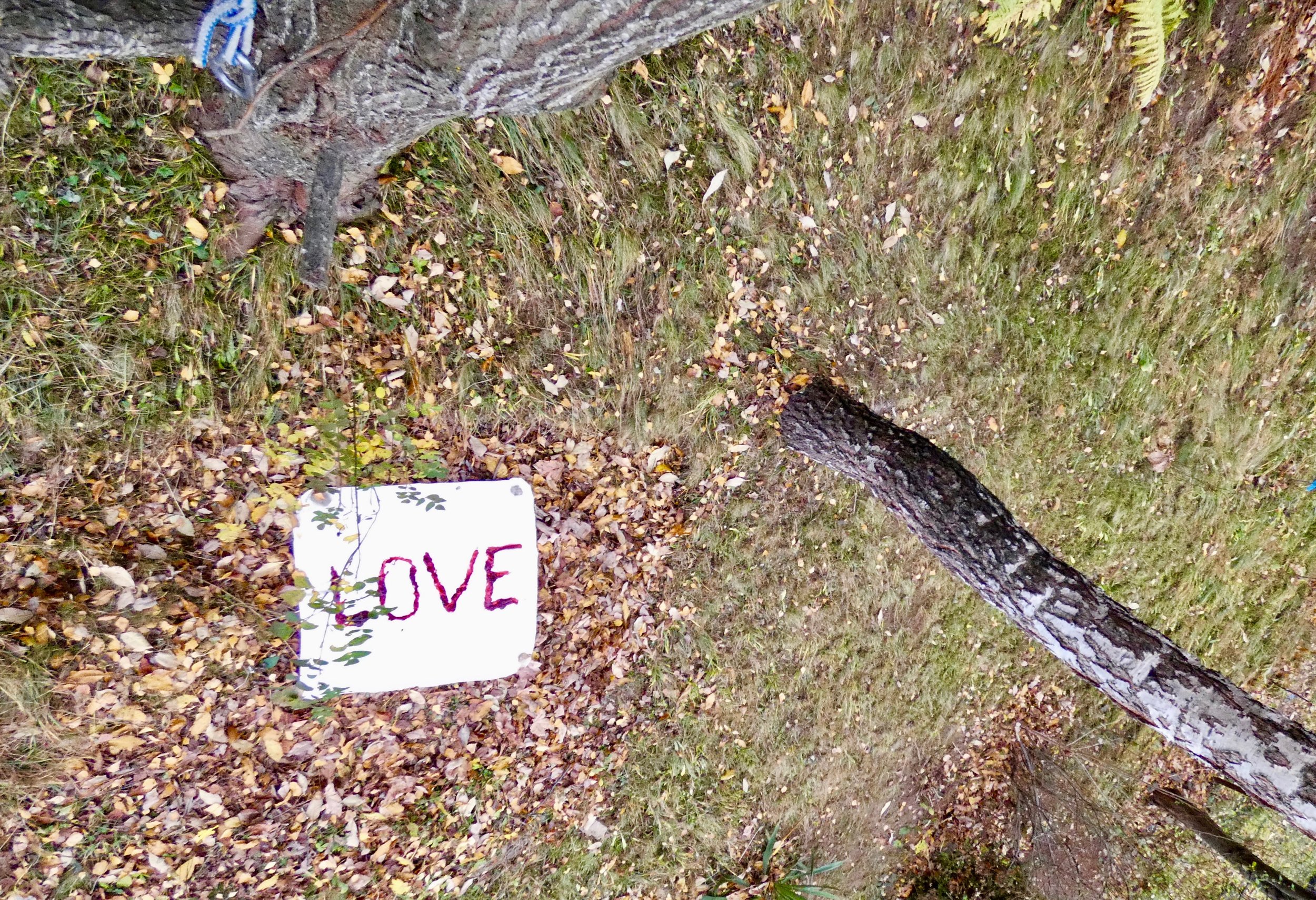

The second work said: WE WILL IMPOSE THE PEACE

It was the title of another poem that had its source into a propaganda poster from 1947. The text was made from sugar. It melted in snow and rain.

VOM IMPUNE PACEA / WE WILL IMPOSE THE PEACE - sugar and thread, 2021

VOM IMPUNE PACEA/WE WILL IMPOSE THE PEACE, sugar and thread, 2021

SEEDS & SPROUTS 2

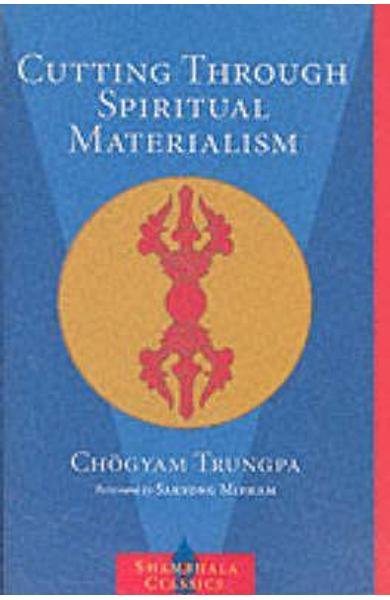

Cutting through Spiritual Materialism was the first Buddhist book I have ever read, about thirty years ago. I do not think, by that time, it was even clear to me that this was a Buddhist work, neither did I know what Tibetan Buddhism was. It was just a yellow book with a red-lettered intriguing title.

As a person who has grown up in a Christian Orthodox culture, all that I knew about Buddhism was from Mircea Eliade's book on the history of religions, or, rather ambiguous and mysterious things on the Japanese Zen. Yet, the book impressed me at that time. It was impressive enough that I still remember two significant concepts proposed by its author, the Tibetan teacher Chogyam Trungpa, together with a funny expression: " the monkey mind".

Monkey, Meissen Manufactory German,1740

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, www.metmuseum.org.

The first concept is the one of spiritual materialism. How does Chogyam Trungpa define it?

It is an attitude towards spiritual quest and development that is modeled after the very Western one of materialism. As the book was written as a response to his Western students, it was supposed to fit their needs. This attitude asks for clear shortcuts and fast and rewarding accumulation of "spiritual assets", such as a certain number of ritual objects, empowerments, or even spiritual teachers. It is seen as a substitute for patient and subtle work that shows very slowly its transformative power. Most of us have it to some extent if we are engaged in a spiritual quest.

The second concept is the one of " basic goodness". To put it simply, this one refers to the fact that every being has a primordial aspect that is virtuous, without any evil stain. This is a quality that exists in each one of us, yet it exists beyond the common conceptual reference. This is the basis of what Chogyam Trungpa calls " the enlightened being".

His concept helped me later to understand to some extent the concept of Buddha-nature.

Because I cannot grasp properly what the Buddha nature is, I will return to the "monkey mind" concept , as Trungpa puts it. It refers to the unruly quality of our common people's minds. We tend to jump from one thing to another, clinging at whatever it is more shiny or perceived as most relevant at a moment or another. Though this might sound like a hopeless situation, the good news is that our "monkey mind" can be trained through meditation. By meditation, Trungpa means particularly the Tibetan form of meditation, not any practice that we can find lately in our Western world under the umbrella of this term.

Since the scope of this text is not to talk about different types of meditation, I will limit myself to say just that I have met a few of Chogyam Trungpa's students and have listened to stories about others, as well as about the Shamballa community he founded. Yet, fortunately or not fortunately, that direction was not my cup of tea ( not my path).

Still, I can say that I am indebted to some extent to Chogyam Trungpa's teachings and legacy. The occasion of encountering some of his wisdom was the discovery of another part of his teachings, those on dharma art. The term might be misleading for most people. If you search for its meaning, it is significant to not follow just your assumptions about what the term meant but to patiently discover bits and pieces from what Trungpa himself passed to his students.

Dharma art was seen by Trungpa as the activity of non-aggression. The artist is just a facilitator of creation that occurs almost by itself, almost like it would be without a creator. I will sumarise what I understood as being essential for the creative process from his point of view. One of the most crucial things in this method is to learn how to look deeply into the space, pretty much like the space around you would be a piece of blank paper. Then, you need to listen to what calls you from there and do your best to help that thing that wants to emerge, to show up into the world – sort of a midwife's job. The artist is just one of the conditions for some artwork to appear in the world, such as the rain being just one of the conditions for the mushrooms or other plants to grow up in the forest. Maybe, some may call it chance encounters, but I believe the process is more sophisticated than that.

However, is beyond the scope of this text to go into depth into Chogyam Trungpa's vision and method of dharma art. What I want to say now, are a couple of things for the reader who does not know yet anything about dharma art.First of all, it is not enough to read Chogyam Trungpa's book, Dharma art, or its more recent version named True Perception, to understand what he intended to do. He uses terms such as art or symbolism, in ways in which we do not usually use in the Western art world.

The book is highly poetical, and, based only on the text, it might be possible that you will misunderstand it.

To get a taste of dharma art method, you need to do some of the exercises that were designed for 'creating' dharma art. The method has some elusive quality, hard to classify based on our Western contemporary art strategies or practices. Moreover, I guess, it would be hard to pin down even according to any traditional Eastern rules of art-making.

What is dharma art?

Instead of trying to explain it, which would be too hard to do just in a few words, anyway, I would prefer to give some references of artists who knew about and most probably used in their working process at least some of Chogyam Trungpa's ideas, exercises, or insights. Some of the most famous were Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. They belonged to the School of Disembodied Poetics from the Naropa University, in Boulder, Colorado. (https://www.naropa.edu/)

Last but not least, regarding my work and effort, I am grateful to David Schneider and Arawana Hayashi, to have given me a taste of what dharma art can be. They were leading a workshop on dharma art in Koln ( in 2010 ) in which I participated. While working on my Ph.D. thesis on "The Crossroads of Contemporary Art with Buddhist Thought – Mindfulness and Selflessness ", I was highly interested to understand more about the possibilities of creating art based on the practices of awareness and mindfulness. That brought me to the dharma art seminar. Some of the assertions and investigations I wrote about in my thesis were based on the experience and insights I got during those days of practice. I could not have seen and interpreted the work of Meredith Monk, which I took as a case study in my research, the way I did, without that experience.

Afterward, I incorporated bits and pieces of mindfulness and awareness-based practices within my methods and strategies of art-making. They are usually not directly visible in any way in the final product, yet, without them, my creative process would not be complete.

David Schneider – former Zen monk and writer – taught me a method that highly influenced my way of writing poetry. Arawana Hayashi, invented, based on the awareness practices she learned from Chogyam Trungpa, as well as her dance training, a practice named Social Presencing Theater. This, very interesting awareness-based method that combines dance and movement with social action, is a method for embodied problem-solving. She is still teaching it in the seminars of the Presencing Institute, all over the world. ( Most probably, she is one of the founders or at least first members of the Presencing Institute, together with Otto Scharmer and Peter Senge, as far as I know)

Going back to my work process, the first two projects where I introduced awareness-based elements into the creative practice, were A Peculiar Tiny Drop and John Murphy Prefers White Wine to Black Pepper. I connected awareness and mindfulness with making images and objects, that further, were inserted within more common practices belonging to 20th century art. The ideas and insights that I had about ten years ago stayed with me and melted into my artistic practice.

https://www.mirelaivanciu.space/work/portfolio/johnmurphypreferswhitewinetoblackpepper

To conclude, it is not an easy task to blend in and work based on such a mixture of criteria and practices that have so different sources and traditions. It will become clearer in the future both why and how I did it , as well as if it is worthwhile to pursue such a difficult and delicate path.

Chogyam Trungpa

Photo was found on https://www.lionsroar.com/beyond-present-past-and-future-is-the-fourth-moment/

SEEDS & SPROUTS 1

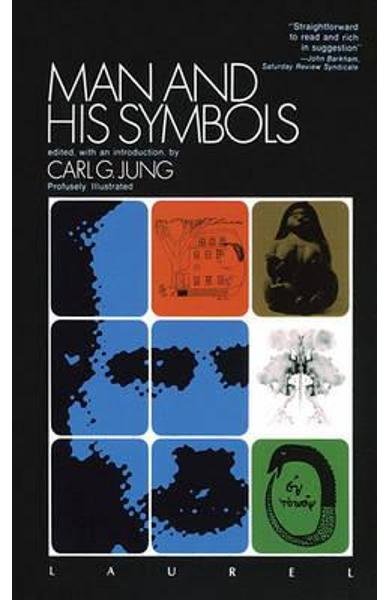

Once upon a time, when I was young, I was studying art and I was very passionate about reading books, I received a small book: Man and His Symbols. It was the last book of Jung, a book that included several essays about his work written by his students.

Since a dear friend gave the book to me, I was very eager to start the reading journey. The first page I laid my eyes on had printed an image of a Tibetan mandala. I was intrigued and liked it immediately.

The image stayed with me many- many years, like a seed that was waiting hidden in a dark corner, waiting to sprout. More than ten years passed.

One day, I was invited by a Chinese friend to take lunch at a small restaurant in Beijing. She was going to meet a person whom, as she told me, I would be joyful to meet. I agreed, happy to join them. I was hurrying through the narrow streets of a hutong while curious and not knowing what to expect.

While waiting for the noodles to be served, I was scrutinizing the person whom I have met and who was sitting in front of me. His round face with vivid and curious eyes and a childish open smile. His presence was completed by genuine laughter that warmed my heart – that really sounded like the one young children often have when they are joyful. He was a young Tibetan, who was spending just a couple of days in Beijing. He was wearing his dark red robes gracefully, as much as his status of a young Tibetan monk. I was delighted to find out that he openly answered my questions, honestly and thoughtfully.

We chatted like old acquaintances. At the end of the lunch, just before we were going to depart, he decided to make me a gift, to take with me home. With both hands in a gesture of respect, he gave me a small thangka painted with a mandala of Manjushri. I was so happy and surprised by his generosity in giving me such a valuable and unexpected gift, that I do not know how I said thank you, for sure, not being able to express well enough the gratefulness I have felt.

The powerful feeling I had regarding the mandala was equally matched by my appreciation of the generous gesture. The desire of being able someday to understand more about the mandala has shown up in my heart. It took less than ten years till my desire was fulfilled. I have seen a sand mandala for the first time in a museum. I even learned a bit about it, though the language barrier had made me lose parts of the explanations.

Since the time I had, did not allow me to go into too much depth, most of what I found out then, has vanished in time, leaving just a deep appreciation for that form of creating art.

I was fortunate enough to see a small old temple with images of mandalas painted all over its walls. I was fortunate enough to see a sand mandala lighted by the butter lamps of an old temple while listening to the chanting of the monks. The desire to learn in-depth how to draw and paint a mandala still stays with me. I just wonder if the next window of opportunity will open up for me soon or not. Right now, maybe I am just planting the seeds for things to come.

In the meantime, one of my artistic interests lately, has been to create impermanent sculptures – very simple texts written using perishable materials. I do not claim in any way that they have the power or deep meaning the Tibetan mandalas have. The way I see them are like small but useful tools in getting acquainted and accustomed to the continuous change that occurs in our lives.

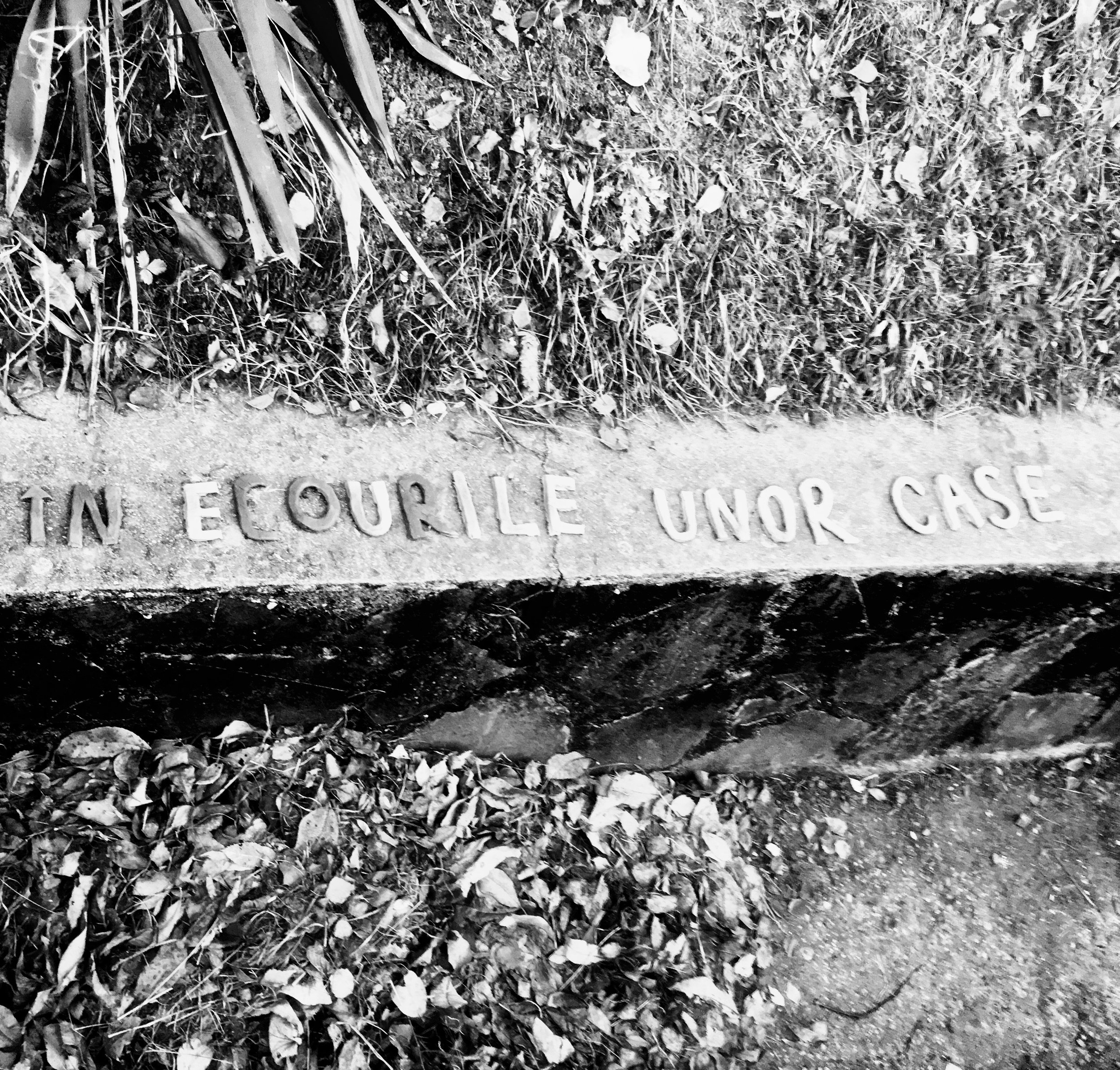

IN SOME HOUSES ECHOES, 2021 - The text is the title of a poem I wrote in 2021 in Romanian language.

This work was made from common modeling clay, placed into the garden, and left to be melted by the rain and wind, and it was the first one of a series of impermanent sculptures.

In the meantime, I made several pieces similar in approach with this. I am presenting here just two of them.

As you might see from the images, I am still coming to terms with the grasping of our ephemeral existence and our continuous change at the most subtle level, which I am most often resisting than not resisting. However hard it is for me to acknowledge it, I am doing my best to sow the seeds for the next windows of opportunity to arise. My feeling is, I still need a lot of work and a bit more renunciation, but since this is a tough subject to handle, I keep postponing it, at least for writing a blog post’s essay.

THAY

I have encountered Thich Nhat Hanh for the first time through his poetry.

One of his most famous poems "Please Call Me by My True Names", is still one of my favorite poems. I did not forget a fragment:

" I am the child in Uganda, all skin and bones,

my legs as thin as bamboo sticks,

And I am the arms merchant,

selling deadly weapons to Uganda".

Those verses touched me. Though to some of the readers, this may sound just like a non-sensical contradiction, for me, it leads towards the conclusion of the poem:

" Please call me by my true names,

So I can wake up,

and so the door of my heart

can be left open,

the door of compassion."

Recently, I mentioned Thay's name to a friend. The reaction was quite critical, the person telling me that his writing was lame. I was surprised. I did not jump to defend him, because I felt he was great enough not to be necessary to be defended. His life and work stood for themselves.

I recalled at that moment that he risked his life to save many lives during the Vietnam war. That is the most well-known fact from his youth deeds. I could not say any word neither about that nor about Plum Village, the community he established in the South of France. I just mentioned this poem. I felt it was more than enough to make you sensitive. I was imagining at that point how easy or hard would be for any one of us to put ourselves in the shoes of the person whom we hate or despise the most in the present moment of our lives. Could we recognize our nature in him or his nature in us?

Could we look one in each other's eyes, and recognize each other's humanity? Could we say, together with Thay, or alone, by ourselves, when we hear one of those hateful or despiteful names, to say ...Yes, I recognize myself in him.

It is very difficult for each one of us. I am aware of it. Only when we are fully honest and try to grasp each other‘s situation, in our own solitude, we can understand both its difficulty, as well as its value. Though, sometimes, it is not quite handy to put yourself in the position of doing it. Maybe, it is because, we are so used not to being concerned with the circumstances of the “evil one”, in our daily lives, we do not even look for it. Most of us do not walk around feeling that we are missing something when we are missing compassion. I am quite confident, that this was not the case for Thay.

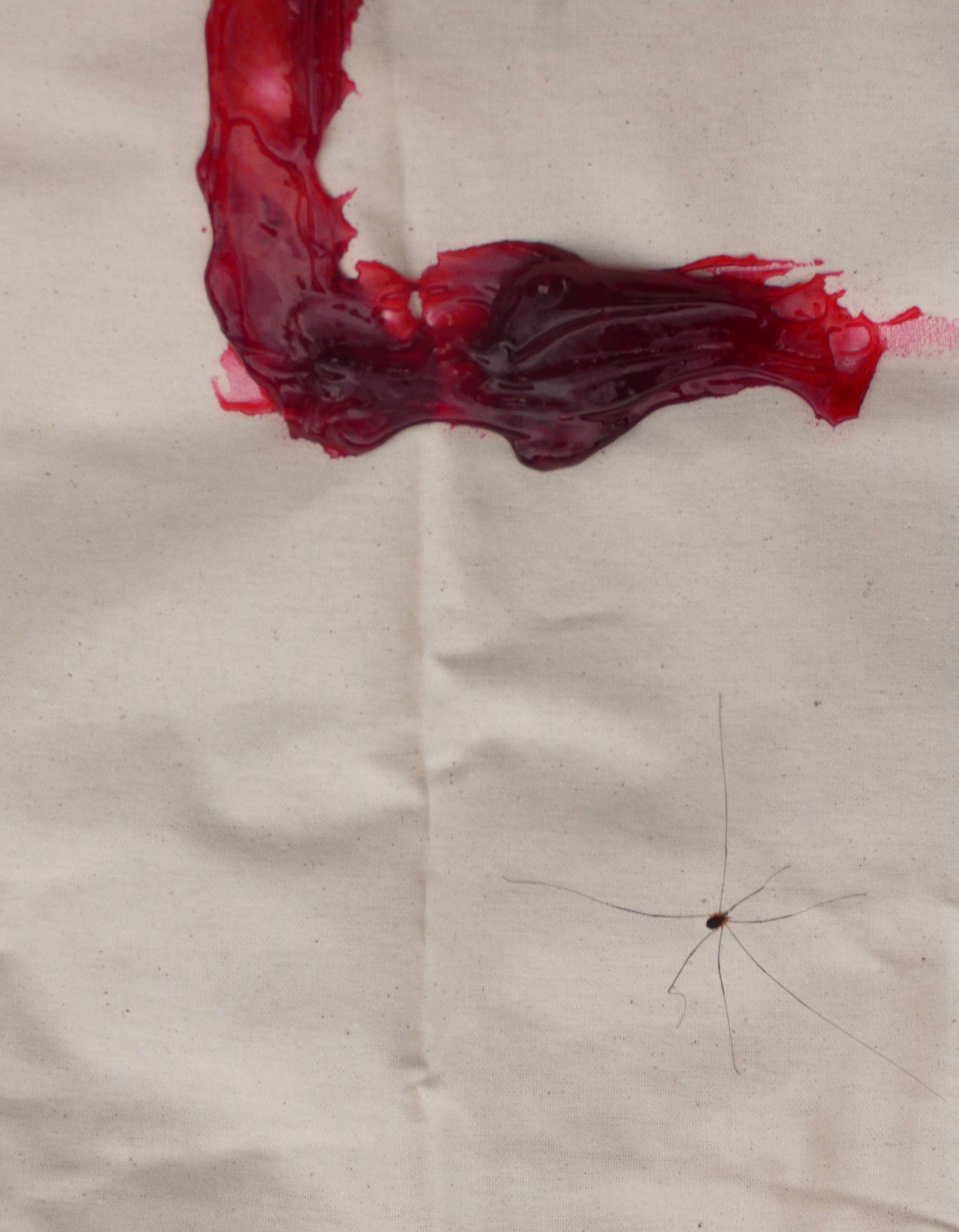

I understand this through my own experience. I do not want to talk about my daily experience, now, but about the way I approached compassion through my work. The closest to this topic I was while doing some photograms – exhibited in the show A Peculiar Tiny Drop. More precisely, I made some landscape-like images, starting from some bits and pieces of matter, of wheat milk for example.

For us, is quite common to give to babies or small children this food made from wheat and milk. I always thought that the softness mothers add to this food, makes it so special. In a very simple analogy, I would say that it is the same about compassion. Its softness makes it so special.

COMPASSION - from the exhibiton A PECULIAR TINY DROP, 2018

In my work, I juxtaposed those images with an embroidered quote from another Buddhist master, Lama Tsongkhapa: " the milk we have drunk from our mothers it is greater than the water in the oceans. "

Maybe it is this particular softness that mothers share with their babies, the quality that nurtures us for the rest of our lives, isn't it?

Maybe that softness was mis-recognized by my friend and improperly called lame. I do not know till today. For me, that softness was easy to recognize in Thich Nhat Hanh's books, such as " The Art of Power" or " Peace is Every Step". I always felt that it is a kind power.

I recognized that softness while I listened once to a dialogue between Thay and a sad little girl who lost her dog. It died. He very beautifully told her, that she could find her dog, if she looks carefully, in the whiteness and softness of the clouds, or the warmth of her cup of tea.

I would say that most of the time, is handier to me to be rather critical, towards others or myself. I need to remind myself in those moments that the power I have, want or need, does not necessarily lie in my harsh speech or judgment. In those moments, am I able to recognize myself in the other, or even properly to see myself? What insight I would gain if I would be able to put myself into the other's shoes? What would be an insight? Insight, in Thich Nhat Hanh's words "is a sword that painlessly cuts through all kinds of suffering, including fear, despair, anger and discrimination." ( The Art of Power -2007: 24).Maybe, I can gain some insight while walking into the other one's shoes, and I can understand that I could have been quite alike.

PLACES OF STILLNESS

For most of my life, I have been afraid or avoiding darkness...the real one as well as the imagined one, the one of the night as well as the one of the spirit.

However, it was just three times in my life when the emotion I felt in the darkness was so overwhelming that it surpassed the fear. There were three moments when I have seen the Milky Way very clearly. There were three very different places - very different moments of my life - yet they were connected through the same kind of powerful feeling.

(2000- 2001)

The first time, I was on the top of a high cliff of the Adirondacks Mountains.

It was the closest to the feeling of sublime among all. Probably the same feeling Caspar David Friedrich evokes in his painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

Yet, in my situation, it was extremely dark on the earth. No human dwellings nearby to throw some homes lightly. You could hear only the sounds of the forest, caused by the movements of small animals that were living around. The fulness and roundness of the darkness had some very still quality.

I felt peace mixed with fear in a very unlikely kinship. Time had frozen for a moment, when neither what happened before, nor what will happen mattered, or at least seemed to be irrelevant.

The Milky Way spilled its white light above my head. Nothing else was present anymore for a moment or two.

Nebuleuse de la Lyre, Paul Henry, 1885

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, www.metmuseum.org.

(2005)

After a couple of years, I was in a Tibetan area of the Amdo province. I was walking in a line of people. We were finding our way through the darkness of a long road from the margins of a village, at almost 3000m altitude. It was a winter without too much snow, yet chilly. The darkness was so deep that while I was trying to watch my feet not stumble through a hole in the ground, I wasn't able to see anything. I could just feel the movement of my body and hear the others' voices that made me feel reassured that I wasn't completely lonely and lost. At some point, I have entrusted my feet with the knowledge that they will follow the path on the ground by themselves and turned my gaze towards the sky. It was there again: the same Milky Way, as clear as before, like a long road, spread over the sky.

I do not recall if I could see the moon as well, yet I was quite sure that, even if on earth all was covered with darkness, somewhere above, a light was shining.

(I turned my face up and down a couple of times and continued the way towards the house in the night, alongside my companions.)

Later, I found this poem I resonate with, and it seemed to be quite related to that situation. "... you walk

happy in no longer fearing mud, rain, nowhereness or night,

not looking for any window, yet indescribably certain

that the lighted window is there, that you'll make it out

however bowed your head, or tight-shut your eyes --- and besides

you keep your head held right, exposed to the rain, and your eyes wide open." Yannis Ritsos, in "Winter Clarity", 1972

(translated by Peter Green and Beverly Bardsley)

(2007- 2008)

The third time I was in Sinaia, a small city of the Bucegi Mountains. This time, there were a couple of small lights of the city, while I was going on the street towards home. The snow barely allowed me to make a path. The sight of the Milky Way light was an unexpected gift.

The silence outside and the stillness of mind merged. The sky was like the surface of a still lake in the middle of the night. The Milky Way was shining in silence.

The movement was absorbed by the snow, while a feeling of tranquility emerged. I was part of that night mountain landscape and that was enough for me.

(2019)

I had to create an installation for the Cuhnia place of the Mogoșoaia Palace. That architectural monument place used to have a hearth in the middle, where the fire was not lit anymore. It impressed me as a place of darkness, despite the beautiful brick walls and cupola that were still there.

I searched for a historical story that would evoke me the same feeling about darkness, that merged the ridiculous with the sublime. I found it and struggle to recover at least a bit from its touching, human quality.

It was a story of people who were evoking images in front of empty frames.

The situation could have been dramatic, ridiculous, or even mad. It wasn't. What made it redeeming?

The power of storytelling together with people's willingness to view imagined landscapes and people.

It happened during the Second World War in the Ermitage Museum, in Sankt Petersburg. Some soldiers were asked by the custodians to help remove the canvases of the precious paintings out of their museum frames, to remove and protect them from destruction. After they accomplished their task, one of the employees of the museum had the idea to thank them by giving them a guided tour through the Flemish department rooms, telling them stories about the removed paintings. That custodian evoked each painting from the room through skillful storytelling based on his visual memory. That story sparked a dialogue about the absent paintings.

I was mind-mapping the elements of that situation: the storyteller, the absent images, and... the stars. I found a relevant quote from Emerson: "when it is dark enough, you can see the stars".

A mixture between real information, historically loaded place, and personal significant stories and imagery have created a fabric of textile sculptures and meaning, enough as to hold the quest for meaningful experiences of people. It was a matter of describing the texture of that darkness, a darkness that may shut us up, but also which brings that particular stillness that allows the stars to shine for us.

Story to See a Star, site- specific work, Cuhnia, Mogoșoaia, 2019

A SAND TRAIL

I was building up a trail, from bridges, tunnels, and roads, made from sand, decorated with pebbles, leaves, and flowers. It was placed in the courtyard, somewhere between the flower garden and the garage. It took me a couple of hours to make the sand stay in place and till each decoration was completed. I do not remember if the wind withered away from the sand and the flowers, or maybe a summer storm. Was it worthwhile the effort? Was it sturdy enough? At that time, while I was about five years old, I did not ask myself if it will last, nor if it matters if it lasts. Much later it occurred to me to ask myself if the universe acknowledges our existence and our dedicated effort? Yet, the impulse and interest for creating temporary constructions from natural materials stayed with me for quite some time.

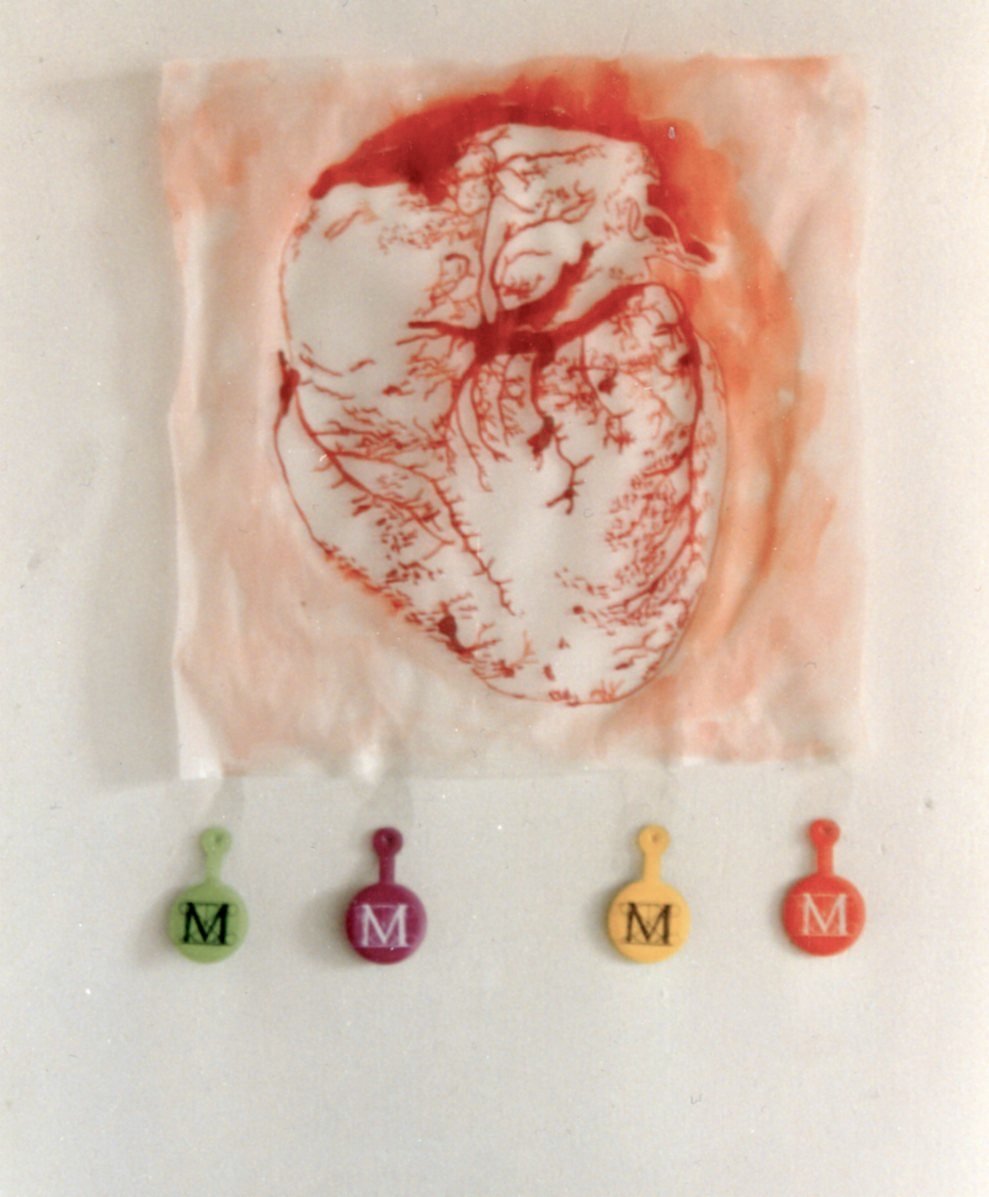

After more than twenty years, while I was completing my graduate studies at the Jan van Eyck Academy, in the Netherlands, I used to place small objects on the wall, next to each other, as a catalyst for a creative moment. Their likely or unlikely juxtaposition was always a reason for reflection, contemplation, or, sometimes, creation of an image, space intervention or installation. One of my professors asked me one day why do I do such ephemeral artistic gestures? She suggested I leave somewhere a permanent trace. I did not do it. Her questioning though has stayed with me quite a long time.

The answer structured by itself along many years of searching and journeying. Yet, its source has been connected with the childhood sand-play, embodying the solitude moments spent in the garden.

When, after about thirty years, I was listening to, or reading about, the idea that all things are impermanent - usually in a Buddhist context - it felt so familiar like I would have all along known it and, those moments of finding out about it were just reasons for remembering the power of that truth.

Still, this feels just like a part of an image that I cannot see fully, or whose meaning is still elusive, escaping my mind's power of grasping it.

Now, I am reflecting back on those moments of change that allowed me some insight into the meaning of change and impermanence, as well as on the sources, resources, or people who helped me to gain some insight. Books, authors, people, or just ideas and concepts, have created a context where my works settled for a while, following the invisible thread that I am making somewhat visible in order to share it with you, the reader.